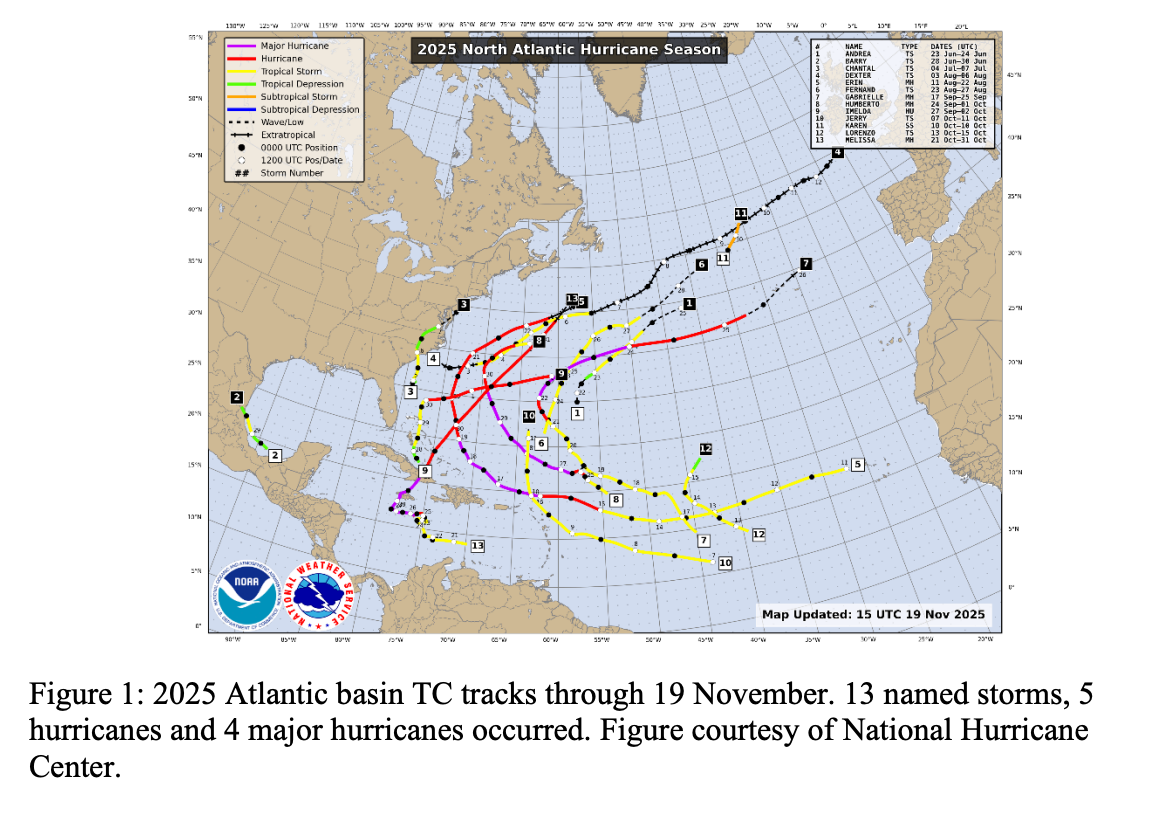

The 2025 Atlantic hurricane season closed with a combination rarely seen in the modern record: an above-normal tropical cyclone activity in the basin, a pronounced lull during the season’s climatological peak, and what researchers described as an "extremely benign" season for continental US impacts.

According to Colorado State University’s (CSU) seasonal verification report released last week, the Atlantic basin produced 133 Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE, firmly within NOAA’s above-normal range, despite generating only five hurricanes and experiencing a three-week collapse in activity from 29 August–16 September.

CSU noted that the season’s structure was highly unusual.

“While the season ended up above-normal… there was a marked peak season lull in activity” during the period that “is typically the peak of the Atlantic hurricane season.” The lull featured no named storms, no hurricanes, and zero ACE, an occurrence last seen in 1992.

The CSU attributes the shutdown to a combination of a dry and stable tropical Atlantic, an upper-tropospheric trough that boosted shear, and “sinking motion over Africa that suppressed West African precipitation and easterly wave amplitude”; effectively cutting off the seed disturbances that normally drive September cyclogenesis.

Despite the mid-season halt, the basin rebounded sharply.

From 17 September onward, the Atlantic generated 93 ACE, the fifth-highest late-season total in the satellite era. Warm sea-surface temperatures (about 0.6°C above the 1991–2020 average) and “somewhat weaker than normal” vertical wind shear provided a supportive backdrop for intense late-season storms, culminating in Hurricane Melissa, one of the strongest hurricanes on record.

Melissa made landfall in Jamaica with 160-kt winds, tying the Labor Day Hurricane of 1935 and Hurricane Dorian for the strongest Atlantic landfall winds ever observed. All 28 ACE in October–November came from Melissa alone, the report states.

For insurers and investors, however, the most consequential metric may be the lack of U.S. loss activity.

CSU concluded that “the hurricane season was extremely benign for continental US impacts, with only one tropical storm (Chantal) making landfall.” No hurricanes struck the continental U.S., the first such season since 2015, despite forecasts calling for elevated landfall probabilities given the anticipated concentration of ACE west of 60°W.

The 2025 outcome underscores a recurring theme in risk modeling: high basin activity does not guarantee proportional U.S. loss experience. With 77 percent of ACE occurring west of 60°W, CSU said that “it is remarkable that the season had very little in the way of impacts besides Melissa.”

An October report from Gallagher Re’s reinforces the unusual dynamic highlighted in the CSU season review.

Despite an above-normal Atlantic hurricane season on paper, the insurance market saw far less loss activity than is typical. Gallagher said that the portion of global catastrophe losses covered by insurers or public insurance entities reached at least USD 105 billion, which is 8 percent lower than the decadal average of USD 114 billion.

According to Gallagher Re, these below-average totals were “largely due to quieter-than-expected tropical cyclone activity in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans,” a finding that aligns with CSU’s characterization of 2025 as an “extremely benign” year for U.S. impacts despite strong basinwide ACE.