Frequency risk has become the dominant driver of insured catastrophe losses, and existing modeling frameworks are struggling to keep pace, according to figures released Tuesday by Munich Re, reinforcing a growing drumbeat of warnings from across the risk markets.

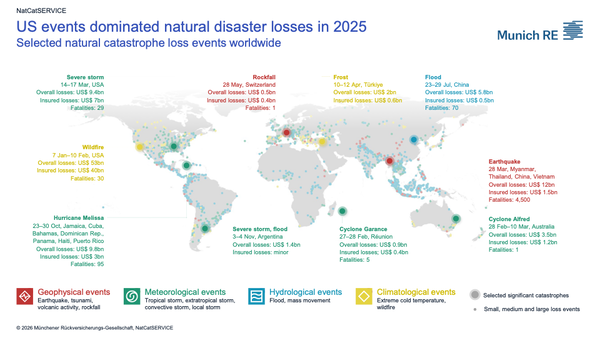

Munich Re’s NatCatSERVICE reported that global insured natural catastrophe losses in 2025 once again exceeded $100 billion — a milestone reached not because of a major U.S. hurricane landfall or a single peak event, but due to the cumulative impact of so-called non-peak perils. Wildfires, inland flooding, hail, tornadoes, and winter storms accounted for the overwhelming share of insured losses last year, pushing these historically “secondary” hazards to the center of the global loss picture.

Losses from non-peak perils totaled approximately $166 billion in 2025, with insured losses of $98 billion, exceeding inflation-adjusted averages for both the past decade and the past 30 years, Munich Re said.

Munich Re’s NatCatSERVICE materials frame 2025 as an increasingly costly year shaped by climate-amplified weather extremes.

“Of all non-peak perils, severe convective storms produce the highest overall insured losses. … losses from wildfires are also rapidly growing. … climate change is worsening risks: rising temperatures and more frequent droughts are making wildfires more likely in regions around the globe,” the reinsurer said.

That conclusion aligns with a broader reassessment underway in private risk markets: frequency risk, rather than tail events alone, is now driving insured catastrophe outcomes, challenging modeling approaches built primarily around low-frequency, high-severity shocks.

This reassessment is not based on loss experience alone. A report from Verisk’s released earlier this year shows that frequency-driven perils now account for nearly two-thirds of global modeled insured average annual loss (AAL), or roughly $98 billion of a $152 billion total.

Severe thunderstorms, inland floods, wildfires, and winter storms — long treated as attritional or background risks — have overtaken tropical cyclones and earthquakes as the largest contributors to expected annual insured loss.

Verisk estimates that global insured AAL has increased not only because exposure values continue to rise, but because event frequency itself has increased materially, with frequency perils claiming a growing share of modeled loss year after year. While climate change contributes incrementally by shifting hazard distributions, Verisk notes that the dominant effect for insurers is operational: more loss days, more claims, and greater earnings volatility across otherwise ordinary underwriting years.

Academic research released by New York University underscores why this shift has consequences well beyond underwriting margins.

Work on catastrophe risk and private insurance markets shows that frequent, spatially correlated hazards are disproportionately expensive to insure because they strain reinsurance and capital-market risk-bearing capacity. Even when risks appear theoretically diversifiable, uncertainty, correlation, and model disagreement introduce pricing markups that cascade through reinsurance and capital costs, ultimately constraining coverage availability and pricing adequacy.

“Increasing climate risk has caused insurance in many locations to become unaffordable or unavailable… the entirety of the increase in insurance offered, and much of the decrease in premiums, comes from reducing the implicit costs associated with insuring spatially correlated risk,” the research concludes.