A new analysis of temperature and mortality data from 30 countries finds that most policies aimed at protecting populations from extreme temperatures are not targeting the real source of the health burden.

The research, led by Stanford University and published last week, draws on decades of subnational weather and mortality data from North America and Europe and concludes that temperature remains one of the largest external threats to human health, responsible for between 5 and 15 percent of all deaths across the studied countries.

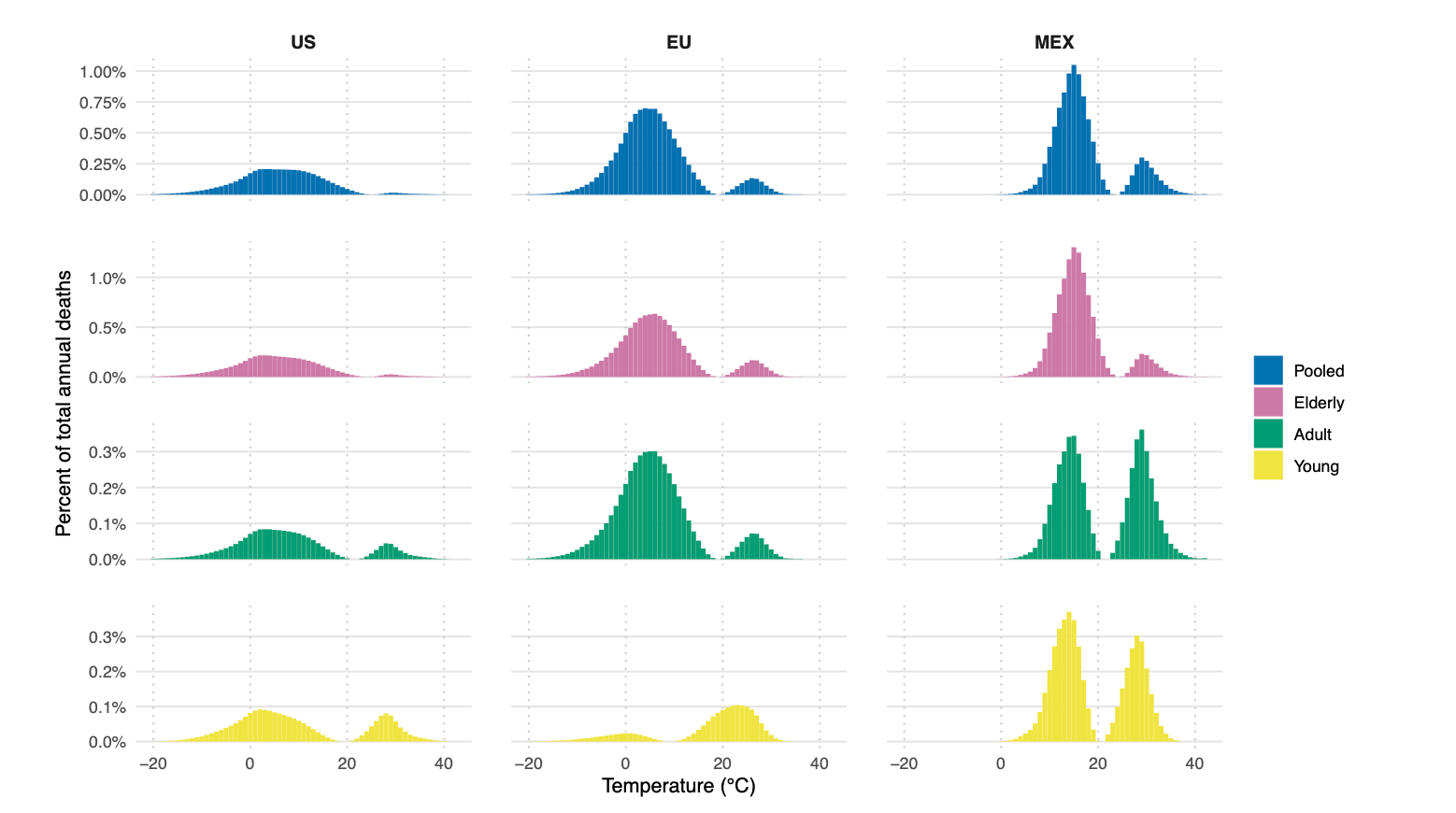

But despite the popular focus on heat waves, the authors show that cold kills five times more people than heat and that most temperature-related deaths occur on “moderate” days.

“Moderate cold and hot days are responsible for a much larger overall mortality burden than extreme cold and heat days,” the report states, “yet policies aimed at reducing temperature-related health burdens tend to focus on the extremes.”

This misalignment has major implications for climate adaptation spending, catastrophe modeling, and risk-transfer strategies that focus on extreme events.

Many insurance and government frameworks define climate-health risk around rare events, heat waves, cold snaps, or record droughts, yet the data show that mortality increases across a broad range of modest temperature deviations.

In the U.S. and EU, for instance, days with average temperatures between 5 °C and 10 °C cause the greatest number of temperature-related deaths. Official warning systems, however, rarely activate below 30 °C, meaning “most heat-related mortality occurs below the temperature thresholds that trigger alerts,” the authors note.

Interventions without evidence

The researchers reviewed interventions designed to reduce the health impacts of extreme temperatures, from heat action plans and urban greening projects to cooling centers and air-conditioning programs. Their conclusion: few have been rigorously tested, and causal evidence of mortality reduction is weak or mixed.

While some randomized or quasi-experimental studies show that heat action plans can reduce heat-related morbidity by 5 to 50 percent, others find no measurable effect, or even increased hospitalizations on alert days, the report states.

Evidence on cold-weather plans is thinner still; one Toronto study found “no discernible effect” on mortality after implementation.

“Despite increased take-up of these plans globally, causal evaluation of their impact on health outcomes remains limited,” the researchers write. “The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence—but we currently do not have the evidence base to prioritize which interventions are most effective.”

A contrast with risk industry assessments

Swiss Re’s 2025 SONAR report released last month paints a starker picture of heat-related risk than the Stanford study.

The reinsurer describes extreme heat as “more deadly than floods, earthquakes and hurricanes combined,” estimating that up to 480 000 people die each year from extreme-heat events.

While then Stanford study emphasize the dominance of moderate temperatures in total mortality and the outsized role of cold, Swiss Re frames extreme heat as the defining global peril, driving losses in health, energy, telecommunications, and liability.

“With a clear trend to longer, hotter heatwaves, it is important we shine a light on the true cost to human life, our economy, infrastructure, agriculture and healthcare system,” said Swiss Re Group Chief Economist Jérôme Haegeli.

The two reports on temperature risk differ mainly in scope: Stanford’s epidemiological approach highlights chronic, under-measured risks across the temperature spectrum, while Swiss Re’s focuses on acute catastrophic heat events and their cascading economic consequences

Non-climate policies that work

Paradoxically, some of the most effective protections against temperature-related mortality have nothing to do with climate policy but broader economic forces, according to the study.

The report highlights strong causal evidence linking affordable health care, reliable energy access, and social-insurance programs to lower heat- and cold-related deaths.

Universal health-care rollouts in Mexico and Colombia, for example, cut cold-related mortality in half, while U.S. programs expanding community health centers reduced heat-related deaths by 14 percent.

Similarly, studies in Japan and the U.S. show that spikes in home-heating prices significantly increase winter mortality—a reminder that energy affordability may matter as much as temperature itself.